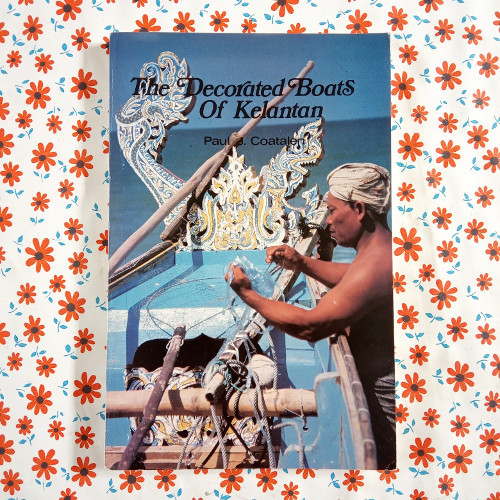

Whenever I visit Mun Kao I raid his library; this time I stole “The Decorated Boats Of Kelantan”, by Paul J Coatalen (Universiti Sains Malaysia,1982).

It’s a survey of the imagery used on Kelantanese boats – which, similar to the Thai tradition, tend to be meticulously carved and painted – as well as a meditation on their symbology.

+

Some neat bits:

“This boat was used once a year by the raja to row about during the rain season … when the Kelantanese had the ceremony of main bah literally ‘to play flood’ which consists of the girls and boys going outside with their best clothes to be drenched to the bones by the downpour. The Kelantanese call it pleasantly the mating season because it is an occasion for boys and girls to meet and see one another.”

My dad grew up in Kelantan; I wonder whether main bah was a thing in his time.

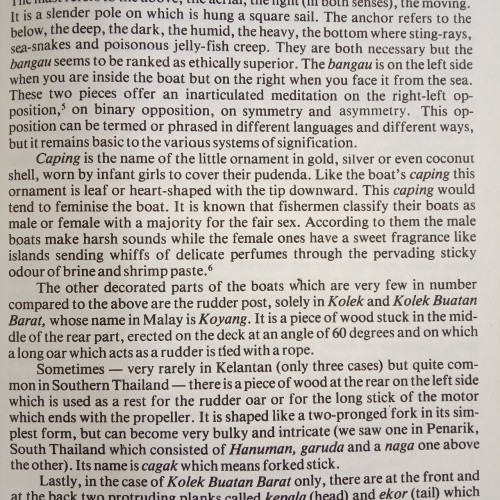

“Caping is the name of the little ornament in gold, silver or even coconut shell, worn by infant girls to cover their pudenda. Like the boat’s caping this ornament is leaf or heart-shaped with the tip downward. This caping would tend to feminise the boat. It is known that fishermen classify their boats as male or female with a majority for the fair sex. According to them the male boats make harsh sounds while the female ones have a sweet fragrance like islands sending whiffs of delicate perfumes … ”

The decorated caping is the “upper part of a plank which goes down to the keel of the boat and which holds the front sides together. To remove the caping would amount to destroying the boat … it is the central part of it.”

It is used as a species of altar:

“The fishermen hang offerings of pinang (areca nuts), limau nipis (lime) and flowers on the pegs that are sticking out of it. Once we saw a seahorse hung on a caping.”

The bangau is a piece of wood on the port side of boats, shaped like a hook, meant “to keep the mast, when not in use, from rolling overboard into the sea.”

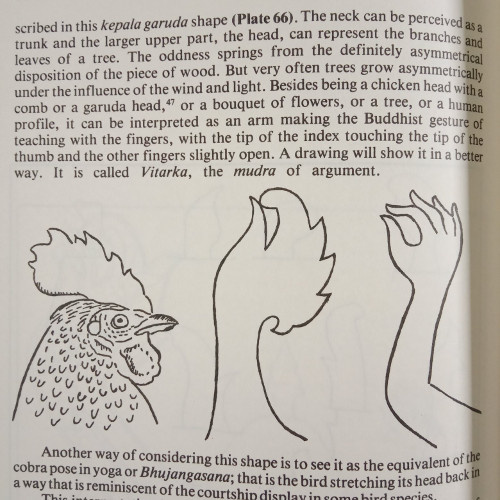

The bangau shape known as the “kepala Garuda” (“Garuda’s head”) is nevertheless often decorated with plant and flower motifs; here, Paul considers the convergence of functional shape, animal form, floral decoration, and human flourish:

“There is a success in the integration of heterogenous parts. It dovetails as it were,” Paul writes.

The book dwells on ideas of negotiation between disparate worlds – as between the animal and the human:

“The official ideology is that the animals are friendly towards men … Snakes, monkeys and birds are paradigms of the different animal classes and it is enough to have good relations with them – ambassadors of some sort as it were – to have good relations with the totality of living creatures … the naga is the animal which is the most problematic for human beings. It will be the one about which the declaration of friendship is reiterated precisely because it is the most real and true danger for human beings.”

Or between humans and the sea:

“One of the main reasons for the boat decoration is the feeling that the place of man is not at sea. Because it is not the territory of human beings a viaticum is needed, a passport, a safe conduct. The fishermen can either reinforce their humanity and be accompanied by their domestic animals, or by their literary heroes or they can disguise themselves as sea spirits, dragons or sea snakes. Or they can do both, a feat which is not so great as that of accommodating Hinduism and Buddhism and the syncretism of both with Islam, let alone with a basically secular and secularising modern world.”

+

Can’t help feel wistful, reading this.

There are frequent asides about how contradictory religious systems sit together, contrasted but dove-tailing, in Malay culture. Paul’s primary informant is the royal bomoh of Kelantan, Nik Abdul Rahman bin Haji Nik Dir. Talking about cultural and religious intolerance, Paul says:

“In Malaysia the problem has so far been avoided. There is some Wahabi influence, particularly in Kelantan and Kedah, as well as fundamentalist reformist trends, the dakwah movement for instance …”

+

Thirty years on, contemporary Kelantan is essentially a theocracy. Main bah is definitely not a thing, any more.

Text by Zedeck Siew. This post was originally published July 17, 2019 on Zedeck’s blog.