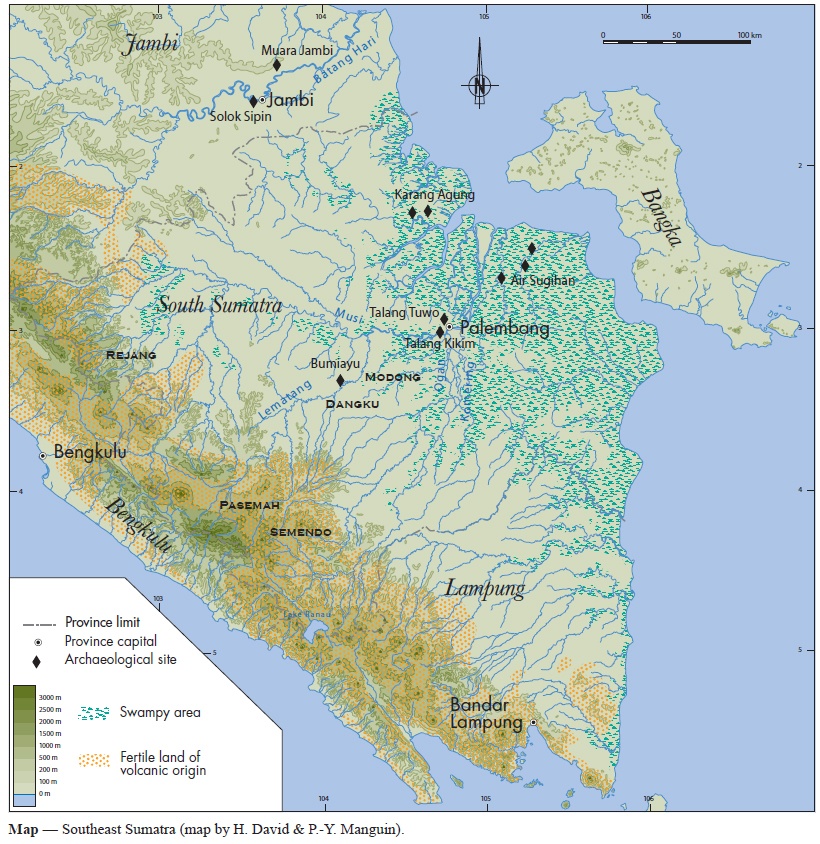

Read this pretty interesting paper by Muriel Charras recently, about food in Palembang. Palembang in Indonesia is where the historical Srivijaya is centered for much of its existence.

Srivijaya lasted from the 7th to 12th century AD and was a major polity in Southeast Asia during that period. It was a center of Buddhism and a major entrepot. It’s been referred to by many foreign sources of that period but because there’s little archaeological evidence left, it was only “rediscovered” relatively recently in 1918.

– Because of various reasons, Srivijaya as a capital in Palembang, while generally accepted amongst scholars, is also contested and argued against.

Here are some notes from the paper I’ve found interesting and summarized:

+ Archaeological records show numerous sites which point to a large city in Palembang, Indonesia.

+ Even before the founding of the large city in Palembang, there are many densely populated settlements downstream, along Musi River.

+ This paper looked into how Srivijaya in Palembang fed its people, given that it had a large and dense population and was a major trading port with travelers, merchants and sailors. The sailors would have stayed in Srivijaya during months of monsoon where they could not sail. Provisions for long ship journeys would also have been needed. The resources required must have been extensive.

Sago

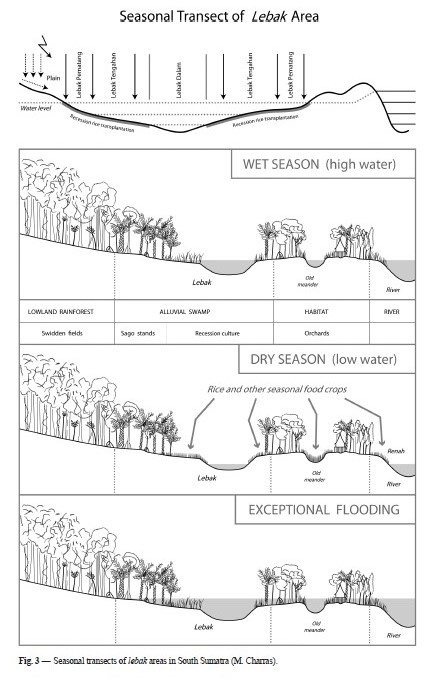

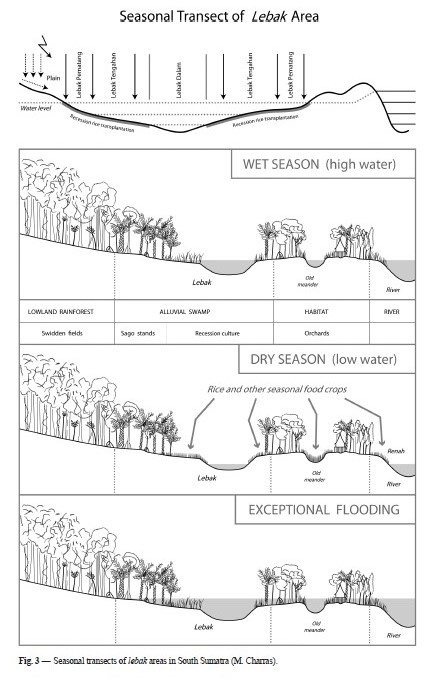

+ Palembang is situated in a very wet and swampy area. The Musi river follows the anticline parallel to the coast and then into a delta of tidal swamps. Basically the freshwater water does not flow directly out but sticks around before slowly breaking into swampy area.

+ The river is fed by two other rivers and during the rainy seasons, it floods to submerge the area, forming freshwater swamps called lebaks.

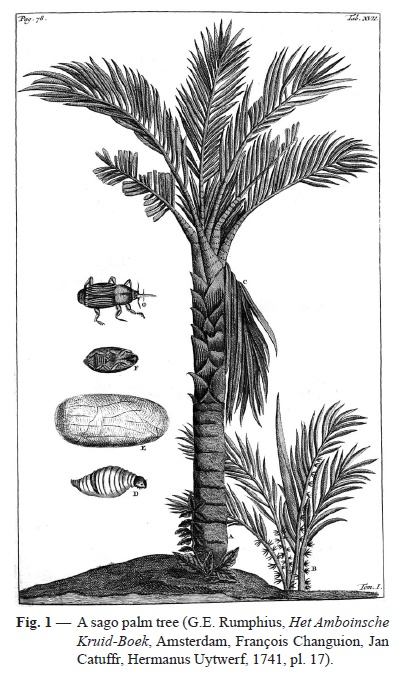

+ These wet, humid and brackish conditions are ideal for the sago palm, which can tolerate a certain degree of salinity, forming a barrier between the forest and the swamps.

+ The pith of the sago palm is starchy and can be processed into edible carbohydrates.

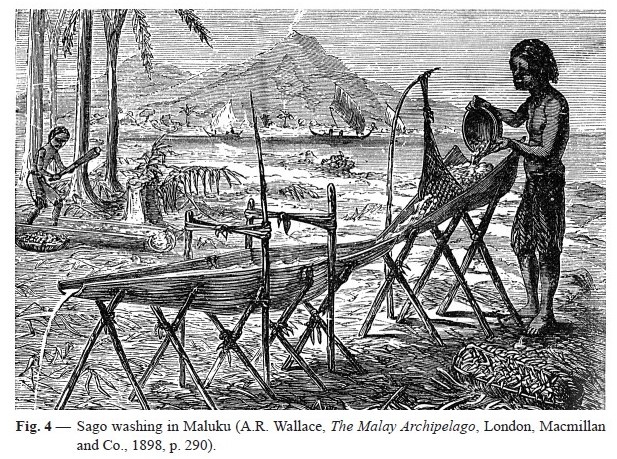

+ I think there are slight variations of techniques but the basic process of getting sago out of sago palm is:

- Fell the tree before it flowers.

- Remove the bark to get at the starchy pith,

- Grind, grate, or chop up the pith

- Gather up that mulchy pith inside

- Wash this mulchy pith get this starchy liquid out

- Let that liquid strain and rest

- The sedimentation from the liquid would be the sago starch which you can make into different forms of sago food products.

+ Here are two videos of it.

Sago processing in the Gulf Province – Papua New Guinea

This is in Papua and these men are beating/scraping the pith into mulch.

Making Sago at Long Beruang, Sarawak, Malaysia

In Sarawak, in this screenshot, they’ve got that mulchy pith laid on a mat . The mat will act as a sieve when they rinse water into the mulch to get the starchy water. Under the mat and the wood, there is a tarp that will collect the starchy water.

In this image above, the man is pouring water into the mulch, the net holds the mulch. Likely the mulch will be massaged to squeeze out the starchy water. The boat shaped thing, likely a palm frond sheath, contains that starchy water, and the sago starch forms a sediment inside while excess water flows out.

+ Sago as a dish and tree, is not as common in Palembang today. This is largely because during Japanese Occupation during WW2, the rice supply was requisitioned by the Japanese, and the locals were forced to turn to massive, unsustainable consumption of sago.

– MK: It’s fascinating how the landscape and diet could be changed massively by human actions and history (and within a span of couple of years). In the paper, it also talks about it was likely human sailors who propagated sago palm all around the region.

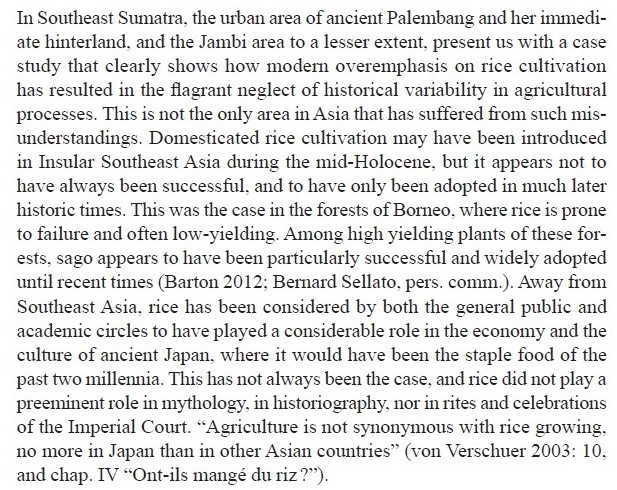

+ Sago flour wrapped in leaves can be kept for up to a month though it slowly gives off a pungent smell.

– MK: I love this so much because Southeast Asia has tonnes of smelly food. Stink-beans, bamboo shoots, fruits, different herbs and leaves, and fermented seafood (and even meat). SEA has loads of pungent strong smelling food and ingredients. It’s interesting to imagine a shared identity of yummy smelliness.

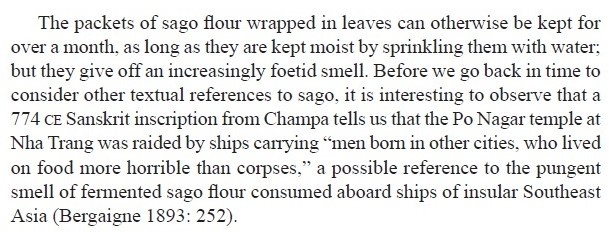

+ Sago flour could be baked in this oven above to get dry sago biscuits that keep even longer.

+ There are inscriptions of the Ruler encouraging folks to plant Sago; pointing to it being more of a domesticated plant. There are even royal gardens of sago.

+ Lots and lots of foreign records of locals eating sago as a staple, compared to cereal, rice, grains.

Rice

+ In contrast to Cambodia, and Java which has longer extended dry seasons and therefore developed irrigated rice farming to support their population, Palembang’s environment is largely wet and rainy, and no records have been found of irrigated rice farming.

+ A likelier possibility is the cultivation technique of using the Lebaks, the freshwater swamps. The freshwater swamps are fertilized by the annual flooding, the soil is loose and no hydraulic devices are necessary to manage drought/water. (Though this technique leaves no archaeological evidence)

+ While this leaves the farmers for other activities during the wet season. it is still risky, subject to rainfall and drought. Overall, rice is a risky crop (Sago is dependable and year round)

+ Even today, this technique is still being used. 60% of the freshwater swamps in Palembang today are planted.

+ There is this paragraph that points out our own perception of rice and it’s association to Asia and Southeast Asia. Basically rice is a difficult crop to grow, risky, requires a lot of resources and does not yield much compared to Sago. Yet the widespread ubiquity of rice in modern days creates this perception that rice is and has long been an integral part of Southeast Asian or Asian society. But that’s not necessary the case and it’s history might not be as long as we’d think.

– MK: What is also awesome is that this critical approach could be extended to so much of our understanding of culture, history and identity.

– MK: By the way, ATTI is also guilty of associating rice with SEA identity, I dont think I’ve drawn any sago yet, but I’ve drawn at least 2 to 3 padi fields.

+ A significant part of the paper also covers the possible dates of when rice becomes prominent in SEA, but I find it a bit convoluted so uhm, read the paper yourself if you are interested!

All images except the top image (from Wikipedia) and screenshots from YouTube are from the referenced paper.

+++

Text by Mun Kao. This post was originally published on July 29, 2021 on the A Thousand Thousand Islands Patreon.